forging fresh yet resonant ceramics

Published in from the fire: a survey of contemporary korean ceramics: an exhibition survey by cho, chung hyun, International Arts & Artists, Washington, DC,

2004.

[Illustrations altered]

Artists, no matter their cultural roots, confront a universal quandary—how to be vibrantly modern and eloquently historical. Ceramicists are steeped in clay, a bewitching material they infuse with structure from an intuitive interplay of personal visions and amalgamations of form, glaze, texture, pattern, and use. Even artists who claim to sidestep history are reacting to their apprehension of existing objects, new and old. The panoply of one’s ceramic experience affects what one chooses to create anew. Whether entangled harmonically or harshly, the past and the present inform each other, enhancing the potential impact of each.

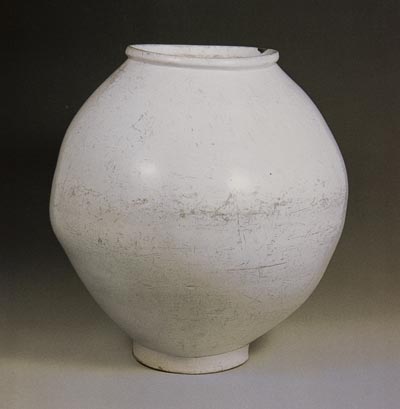

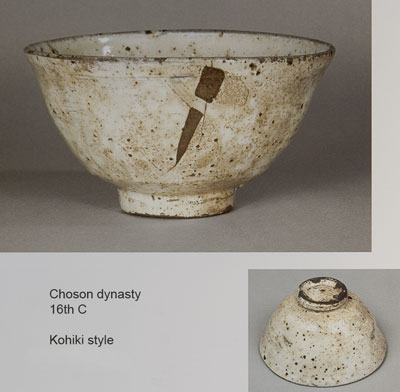

Korea is blessed with a stunning oeuvre of ceramic accomplishment that provides a deep heritage that remains attuned to contemporary sensibilities. This rich reservoir of ceramic grammar has great emotive range, from the gray restraint of Unified Silla (688-935 AD) to the elegance and softness of Koryŏ (935-1392) inlaid celadon. There is significant grist in the robustness of onggi jars and the simplicity of deep black and brown glazed stonewares. The directness and looseness of Chosun (1392-1910) punch’ŏng continues to impel reflection. The Confucian solidity of Chosun white porcelain still expresses a purity born of form and monochromatic color that nonetheless bulges with the inherent flaws and compromises of living—reminders that irregularity and fault can be embraced as exemplary marks of resilient character.

White Porcelain Jar H -" x W -"

Old and new Korean sources underpin much of American ceramics, sometimes transferred directly, other times through the membrane of Japanese derivations. For example, medieval Korean punch’ŏng ricebowls comprise one essential component of the still influential twentieth-century international Mingei aesthetic of natural materials and unpretentious folk art. Hidden but equally influential in America is a long pedigree of Korean concepts veiled within the core of Japanese ceramics. Much of this lineage was securely established by the physical transplantation of Korean potters and their families to the Japanese island of Kyushu after the pottery wars of the late 1590’s.

Today most artists move voluntarily, personally driven to intertwine if not confound cultural currents. One’s artistic genealogy need not be culturally based, merely heartfelt and honed, elemental passions shorn of sentimentality. Influences remain intertwined beyond unraveling once it is understood that more than several of the influential Korean artists in this exhibit have studied and/or taught in American university art programs—or that American artists derive significant components of their aesthetic vocabulary from Korean accomplishments. As a student in the early 1980’s, I observed visiting Korean onggi potters deftly making large storage jars during demonstrations in Washington, D.C., yet one more reason to travel to Korea which I did in 1986.

Onggi Jars

It has been said that the past is merely a foreign country. Enter many American art museums and one will find exhilarating selections of historic Korean pottery. Or wander the galleries of New York City and one is liable to encounter the work of living Korean ceramic artists. In fact, the range of Korean ceramics—as well as other Asian, European, and American objects—encountered in galleries today isn’t any different in concept from perusing pottery in 1600 in Kyoto, Japan. A shopping spree could require choosing among domestic wares such as fresh, textile derived Oribe-ware or anagama-fired Shigaraki-ware as well as foreign glazed objects made in Korea, Vietnam, and China. [1]

Ceramic internationalism is not new. Ceramics has always demonstrated a complex interplay of the foreign and the local, the past and the present. Periods of innovation are often evidence of a mélange of external influences. Seeds of appreciation for the directness and complexity of woodfired glazes, for instance, have widely taken root within the United States due to museum collections, visiting foreign artists, and American artists returning from apprenticeships abroad. [2] Thus, Korean woodfired tunnel kiln technology, which had been transferred to Japan in the fifth century, finally spread across America in the 1970’s. This type of kiln (frequently known by its Japanese name, anagama) has been resurrected because even now it provides a sophisticated and irreplaceable tool for aesthetic communication.

Korean tunnel kiln

Conferences and biennial competitions in Korea, Italy, Japan, the United States, and elsewhere draw participants internationally, congealing aesthetics while highlighting native singularities. Works that inspire are neither merely respectful of the past, nor totally beholden to the unrooted genre of international ceramic sculpture. Stirring work insightfully reflects history and the self with verve, freshness, and deep feeling.

-caption-

It is too often forgotten that pottery is an almost universal—although distinctive—cultural endeavor without an inherent national identity. Thus, clay can faithfully capture and convey the idiosyncrasies of the culture within which its form was conceived. Without doubt, ceramic objects can be too derivative, but such instances are more cases of bad art rather than markers of improper influence. The only valid claim supporting the primacy of indigenous traditions is that ingrained conventions of form and pattern are easily interpreted. They compose a common and understandable language. Yet, sooner or later, quickly or slowly, new feelings, ideas, shapes, embellishments, materials, and techniques always infiltrate from afar. Go far enough back in time and the “native” is always transformed into a foreign transplant. What was once different, non-local, and less interpretable ultimately becomes adapted to local needs, nuances, and visions.

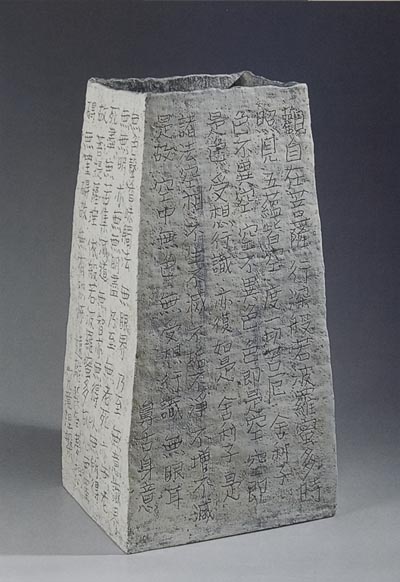

Soo Jong LEE H 53cm x W25cm

iron brushed punch"ong jar, onggi claybody

Today, American makers and users can be as knowledgeable about Korean ceramics—or any other foreign or historical genre—as Koreans or others can be conversant with American artistic accomplishments. Ceramics has always been an admirable vehicle for reciprocal cultural exchange. For those not yet exposed to contemporary Korean ceramics, this exhibition has the exciting potential to fundamentally enlarge perceptions of the nuances of ceramic expression.

American artists will learn something profound if they discern the historical roots feeding the distinctive visions expressed by the best works in this exhibition. For instance, familiarity with corner-flanged Chosun ritual bowls and of nineteeth-century faceted ginger jars ricochets to reveal the deft creativity of Yik Yung Kim’s faceted porcelain bowls. Punch’ŏng with onggi clay is an articulate mesh of fresh slip, roughly applied and resonant iron brushwork that blossoms in Soo Jong Lee’s jars.

Yik Yung KIM H -" x W -"

Ceramics is an exquisitely complex and abstract mediator. Superbly suited to resolve the uniquely personal with the broadly cultural, ceramics can also negotiate eloquent tensions constructed between the local and the foreign. Because people universally share similar dreams and demons, artistic heritage is a reservoir of sustenance open to all. Sometimes the artist born to a tradition provides a superb interpretation, yet this never precludes any so-called “outsider,” embracing the essence of a genre, from being extraordinarily insightful. Often individuals from other disciplines or other cultures provide fresh appreciations and alternative vantage points that permit innovative choices and unexpected conceptual leaps. In the late 1800’s an American zoologist, Edward Morse, was the first to investigate Japan’s shell mounds leading to the discovery of extravagantly embellished Jomon pottery. A respectful interchange permits outsiders to remind insiders of realms less explored.

In ceramic discourse, American concepts for Koreans are as relevant as Korean sources for Americans. Viewed with respect and connoisseurship, each holds promise. Influences are bi-directional, but the results will remain vibrantly distinctive. Nothing, of course, is guaranteed. Any particular result may be misguided or brilliant. Yet in both cultures works that passionately integrate historic nuances with personal visions hold the strongest possibility for speaking eloquently about contemporary feelings.

Notes:

1. See Louise Allison Cort, “Shopping for Pots in Momoyama Period Japan,” in Morgan Pitelka (ed.), Japanese Tea Culture: Art, History, and Practice, Routledge Curzon Press, 2003.

2.See Louise Allison Cort, “A Short History of Woodfiring in America,” in Great Shigaraki Exhibition: Rediscovery and Revival of the Beauty of Yakishime Stoneware, Museum of Contemporary Ceramic Art, Shigaraki, Japan, 2001, 182-192. Reprinted in The Log Book, issues 9-12, 2002.