The Inescapable, Indivisible Essence of Pottery

Published in The Art of African Clay: Ancient and Historic African Ceramics, Douglas Dawson Gallery, Chicago Illinois, 2003.

How can objects created in earlier epochs, from our own or other cultures, touch us so deeply? Why is a double-necked water jar from the Mambila (Cameroon), a satin black Zulu ukhamba for brewing beer, or a softly bent-necked pouring bottle from the Matakam (Chad) so evocative? Can pottery whose origins spring from foreign cultures or distant times actually be germane today?

Pottery’s potency lies in its resolution of dual realities. There

is the obvious sphere of physical use: the realms of filling, pouring,

carrying, or perhaps brewing. Then there is the sphere of abstract use:

the metaphorical realms of sustenance offerings, status delineators,

emotional containers, or vital funerary accoutrements within a given

cosmology. For pottery this duality of abstract and physical use confers

both irreplaceability—no other medium can take its place—and

indivisibility—the utilitarian, spiritual, and aesthetic are forever

intertwined.

All photos are by Paul Lecat, copyright by Douglas Dawson.

Yet pottery’s essential utilitarian character can cloak the abstract essence through which these African vessels serve the soul. In Western cultures that have separated art from daily life, the seam of this duality is prone to being ripped apart. There are art historians whose perceptions are limited to pots as “merely physical containers,” anthropologists who treat pottery solely as data reflecting cultural interchange, even art critics who assess strictly in terms of purified formal aesthetic qualities such as color, volume or patterning. As in the ancient Indian parable, “The Blind Men and the Elephant,” all are exploring only one isolated aspect of a complex creation.

It is true that these objects cannot be experienced in their original

contexts. We are missing something by not carrying the day’s drink

in a Toussian water jar or by not storing an entire season’s grain

in a storage jar. Even exhaustive knowledge about a Cézanne distillation

of Mont Sainte-Victoire or a Jackson Pollack flung-pigment painting does

not permit our experience to match the artist’s. As objects leave

their place of origin—whether yesterday, one hundred, or five thousand

years ago—they begin to lose specific traits. It is forgotten who

made them, when they were made, how they were used. (fn

1) Even

if makers are known, as with documented self-taught or Art Brut artists,

their

conceptual

system still may be impenetrable. Yet the art remains extraordinary and

compelling. (fn 2) We seem destined to stitch

together glimpses of each story; we learn about other times and places;

we interweave

our own immediate,

personal, and vibrant relationships. Art is always moving away from its

origins, suffering an inevitable loss of context. However, beneficially,

the accretion of time permits related objects to be newly grouped, bridging

time and geography. Delineations of excellence evolve, but current masterpieces

are never mute. The eloquence of the hands, eyes, and hearts that made

these objects still captures our passion.

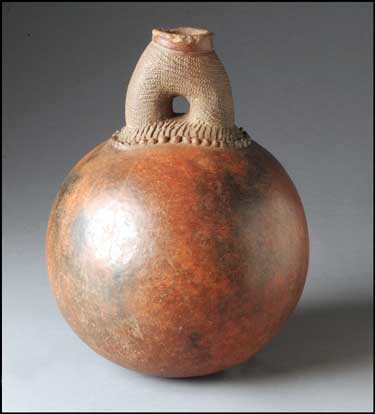

Ewe (Ghana or Togo) H 8.5" x W 5.5"

If

forced to generalize, I would argue that these stunning African objects

convey a fundamental sense of earthiness and immediacy. This pottery

embodies nature as it also manipulates nature. The unadorned qualities

of clay and earth are embraced in these pots. As a material deftly

handled, earthenware is less prone to the afflictions that can overwhelm

higher-fired clays concealed with thick, colored, and seductive glazes.

Incorporated in these African vessels is a unified spirit of spontaneity

and assurance, whether rough and unrefined or elegant and vigorous.

Early art that is articulate speaks to us because it is attuned to current necessities. Our common humanity explains both our need and our ability to draw insights from the creations of others. No matter how dispersed the origins, objects coalesce as pertinent answers to perennial, duplicative questions. In 1962 George Kubler, an anthropological art historian, adroitly analyzed the history of ideas and art objects in his seminal book, The Shape of Time. Replacing progressive and linear theories of stylistic change, Kubler argued that an art object “points to the existence of some problem to which there have been other solutions and that other solutions to this same problem will most likely be invented to follow the one now in view.” (fn 3) For Kubler, objects are reinvented resolutions to enduring problems. For artists—whether potters or painters—the modern configuration of tradition embraces objects clustered closely in meaning but diverse in material, cultural, and temporal origins.

Tutsi, Rwanda H 9" x W 6" and 6.5"

This dynamic grouping is legitimate because human character and biology

change far more slowly—if at all—than do technology or economics.

We are far closer to our historical or foreign brethren than we usually

imagine. We share a remembrance of our common destiny of death, our equivalent

senses of hunger and satiation, and our inescapable emotions of joy and

sorrow. Pottery flourishes among these existential facts. Art in all

its manifestations exists as an essential mediator of existence. (fn

4)

There is a common mistaken belief that artistic endeavors demonstrate

progress, perhaps because we are so used to witnessing technology advance.

Yet if art truly progressed like technology, then today’s art objects

would clearly outshine everything in our museums. Incontrovertibly, they

do not. Kubler’s perspective is corrective. One chain of solutions

in relation to another coherent chain is not inherently progressive or

sequential. The closer we examine a sequence of vessels, the more unique

each becomes, neither explaining what came before nor predicting works

yet to come.

Zulu H 15" x W 19"

At first, all Zulu beer fermentation jars seem stylistically similar. But in fact, they differ by maker and by user. (fn 5) All potters know that the manners in which they handle the clay—their personal signatures—are almost impossible (and undesirable) to erase. When first made, each Zulu jar expressed accepted norms, regional variations, and, I would argue, recognizable individual aesthetic innovations. The patterns of amasumpa (raised pellets), probably a royal prerogative, once expressed other specificities that are forever lost. Yet, as handmade artistic objects, each vessel remains unique and alive. Kubler compares style to a rainbow: once we reach the source it disappears. (fn 6) Vessels are not transparent windows into the past, but membranes that express their own properties and qualities. For an artist, historical pots are a contemporary reservoir of inspiration. They enlarge the vocabulary of a common ceramic language and enable new methods of combination and communication.

Nyonyosi-Yatenga, Burkina Faso H 15" x W 11"

Appreciation is not simply a matter of aesthetic intuition, though intuition is an essential sensibility. Comprehension is also an accretive educational process of connoisseurship. Determining virtuosity partly emanates from comparisons and references within the universe of known clay vessels. What carries forth my passion in these African pots is a ricocheting energy between each vessel’s overall aura and the nuances of inventive phrases freshly spoken. Densely handled rims, textured and whorled patterns, and sculptural necks are all fecund, provoking dreams and gestations of new recombinations within personal motifs.

Tasting the essence of pottery requires memory excavations; retrievals

of patterns formed by using and seeing countless other objects, man-made

and natural. (fn 7) Elements are not necessarily

harmonized, as in discordant but emotive music. Disentangling may begin,

perhaps, with the clay’s

character. Textural impurities in these African pots impart an assertive

sense of directness, an emotional acceptance of earth. Vessels in this

exhibit with more purified clays bespeak elegance; material refinement

elevates emotional distance. An enclosed volume may be bursting or focused,

the upward visual thrust—from a base or a higher area of transition—forcible

or subdued. Where the fullest point of a form is positioned contributes

to impressions of stolidness or loftiness. The neck’s resolution

of the pot’s shoulder may be abrupt and exaggerated or fluid and

graceful. Texture, color, the sensitiveness of stance (base or foot),

and so forth all contribute meaning. In an eloquent vessel, all of these

facets work in conjunction, admirably tensioned. The parts compose the

whole but do not explain it. Creating a living pot demands personality

rather than consistency or reassurance. For instance, refinement contrasted

with irregular yet decisive handling speaks more potently than overall

precision that obliterates traces of the potter’s presence.

Luba H 18" x W 11"

Arthur Lane’s slim 1948 book, Style in Pottery, reflects useful

common discourse: “In using such words as lip, neck, shoulder,

belly to describe the shape of a pot we acknowledge its likeness to a

living thing.” (fn 8) Pots reflect not only

universal human character traits—anguish as well as vigor—but

also the diverse shapes and protrusions of the human body. This is not

false anthropomorphism,

but a primary instance of pottery’s unique abstracting capacity.

As a metaphor for the human body and as an object typically sized to

fit the embrace of our hands, pottery is a close, manipulable presence.

These attributes confer irreplaceability. They set pottery apart from—but

not below—untouchable, monumentally sized art, such as paintings

that only fit museum-sized walls. Yet even with such generalizations

by genre, approachability varies.

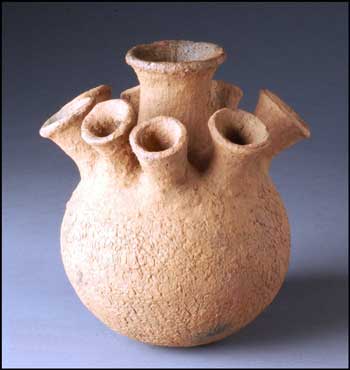

Cameroon H 18" x W 15"

Many vessels in this exhibition manifest intimacy as a heightened, palpable

quality. Mounded earthenware firings that maintain the visibility of

the hand-forming methods used and that magnify the clay’s physical

tangibility intensify intimacy. A closer insistent presence also derives,

at times, from unexpectedness—an unanticipated double neck, an

unusual shaping of a shoulder or foot, looped handles that seize exterior

volume, or a convoluted yet coherent patterning. Touch is inescapably

vital for experiencing all pottery because of the centrality of its use.

Yet this pottery seems to additionally beckon, to demand even more intensive

contact when conveying heretofore-unseen expressive constellations. Touch

unlocks nonvisual dimensions: heft, warmth, or the wet evaporative seepage

of an earthenware water jar. Turning a pot in our hands creates tactile

sensations of three-dimensional rhythms, the syncopation of irregularity

in form. Full creative encounters entail repeated but nonduplicative

use. Interaction transforms both the object and us.

I have previously written about the poetics of primitive pottery, the

value of vigorous and spiritual art, but no matter how it is explained,

primitive negatively connotes simpleness and backwardness emanating from

cultural arrogance. (fn 9) It is our ignorance

of the abstract sphere of pottery that is unsophisticated, not the objects

themselves. To take one example,

surface patterning is simply not superficial. So-called ornamentation

is not an addition or an afterthought, but an indivisible component of

completion and fulfillment. (fn 10) Perhaps if

we conceptualize pottery surface as skin we can convey the essentialness

of surface markings. Skin is

indispensable to life, the central mediator between our internal nature

and the external natural environment. Treatments to each vessel’s

skin are integral to these forms. Even when symbolically unfathomable,

these clay skins are reminiscent of body markings, wood carvings, textiles,

braided ropes, and animate creatures.

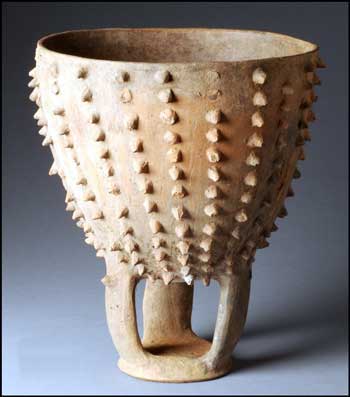

Kirdi/Chamba H 22" x W 14"

Significant pottery reveals an extraordinary rapport of form and surface

image. What is admirable about these African vessels is not the result

of a particular technical flourish, stylistic rarity, technological

accomplishment, or royal provenance. Esteem is due to an intense

expressiveness of material

and usability. The ineffable is real but not fully describable. The

physical-cum-abstract use of pottery is ongoing. Historical objects

and freshly made art can

be equally potent. Neither can be fully eloquent in isolation. Part

of the past is modern and alive. Part of the modern partakes of the

past.

Pottery, inescapable and indivisible, new and old, deepens perception

and enlarges imagination.

Notes:

1. We should never replace our ignorance as to the utilitarian-aesthetic-symbolic life of an object with the belief that no such complex creative nexus exists. Nor should we mistake our inability to discern who actually made an object with the assumption that the object was anonymously generated. We should recognize the speciousness of any claim that the genesis of another culture’s material objects does not involve any individually chosen aesthetic decisions. Recent scholarship has begun to correct for these myopic views, documenting in Africa, for instance, the wide creative latitude exercised by specific individual makers creating within sophisticated cultural traditions and needs. See for instance, Sally Price, Primitive Art in Civilized Places (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), particularly chapters 4 and 8.

2.For an evolutionary explanation as to why we fundamentally

respond to “outsider” art—or any art, including pottery—see

Ellen Dissanayke, “Very Like Art: Self-Taught Art from an Ethological

Perspective,” in Self-Taught Art: The Cultural and Aesthetics

of American Vernacular Art ed. Charles Russell (Jackson: University Press

of Mississippi, 2001), 35-46.

3. George Kubler, The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History

of Things (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962), 33.

4. Ellen Dissanayake, Homo Aestheticus: Where Art Comes From

and Why (New York: The Free Press, 1992).

5. Frank Jolles, “Zulu Beer Vessels,” in Tracing the Rainbow: Art and Life in Southern Africa, ed. Stefan Eisenhofer (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche) 306-319.

6. Kubler, 129-130. Also see Kubler’s introductory comments on the history of art and the place of the artist in The Art and Architecture of Ancient America, 3rd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 37-45.

7. Philip Rawson’s treatise, Ceramics, the only in-depth inquiry in English to delve into pottery’s aesthetic grammar, explores the symbolism of the many physical aspects that compose a vessel. Philip Rawson, Ceramics (London: Oxford University Press, 1971).

8. Arthur Lane, Style in Pottery (London: Oxford University Press, 1948), 10.

9. Warren Frederick, “The Poetics of Primitive Pottery,” in Ceramics: Art and Perception, 20 (1995), 43-45.

10. Rawson for instance, notes that “we have to make the effort imaginatively to put ourselves in the place of the users, seeing the symbols as having not the content we might see in them…but as elements in a vivid life of sensation and emotion.” All patterns “must have been meant…to add value and spiritual effectiveness, through their evocative overtones, to the ware in the eyes of its user” (161, 165).

Cesar Paternosto,

an abstract painter and sculptor, has clearly and extensively argued

that for many

non-European material objects (fiber,

clay, stone, wood, or metal) surface patterning itself is the central

art. Paternosto’s specific convincing example is for the centrality

of geometrically patterned Andean textiles as that culture’s primary

and most essential symbolic language. He also explores these textiles’ direct

influence on 20th century artists such as Paul Klee, Adolph Gottlieb,

and Barnett Newman. Cesar Paternosto, Abstraction: The Amerindian

Paradigm (Brussels: Societe des Expositions du Palis des

Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, 2001).